Strategic Research Agenda section1

Introduction

Background

Developing an OHH research agenda and implementing its findings enables Europe to promote the health of its people, the European regional seas and the wider global ocean.

The aim of this Strategic Research Agenda (SRA) is to present an approach and framework for creating the required Oceans and Human Health (OHH) research capacity in Europe, and to outline a critical agenda for OHH research for the short and medium term in order to achieve that capacity. It is not the aim of this SRA to endorse any specific approach.

The SRA focuses on three main target action areas:

- Sustainable seafood and healthy people;

- Blue spaces, tourism and well-being;

- Marine biodiversity, biotechnology and medicine.

Several important cross-cutting themes arise from these target action areas, including climate- and global change, pollution, ocean literacy and citizen science, equity and equality, sustainability, innovation and employment. These topics are not discussed explicitly but are addressed as relevant within the three main areas. The SRA presents the importance of each of the three main areas, outlines key research questions that need to be answered within an indicative structured timeline, and highlights the needs (in terms of research to inform policy, capacity and training, and for the public) that should be considered. The SRA highlights overarching recommendations for research needs that apply to all areas of OHH, and the measures of success in achieving the required capacity.

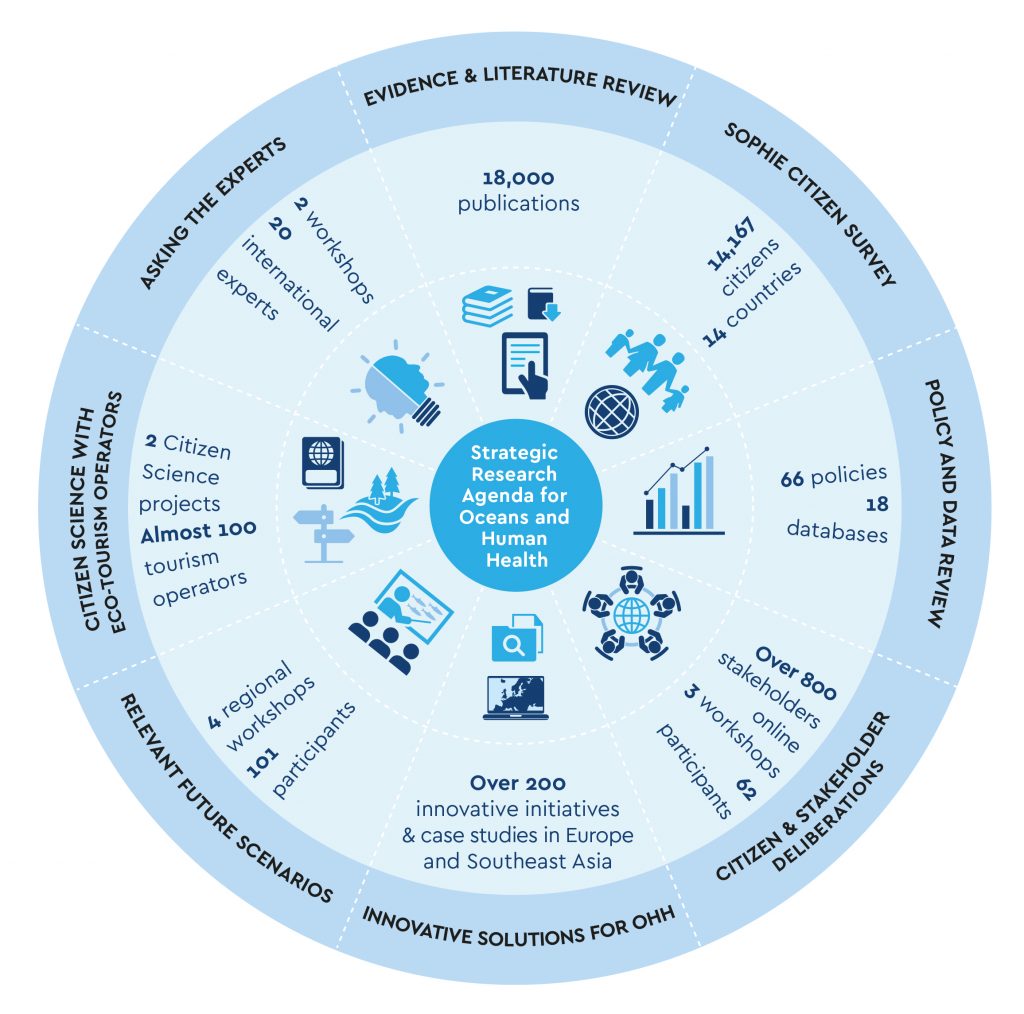

The three main target action areas and research questions were identified by a group of 20 transdisciplinary and international experts, who formed the SOPHIE Project Expert Group(1), during two dedicated workshops in April 2018(2) and January 2019(3). The action areas were then further refined using input from all other SOPHIE project activities including input from citizens and other experts. Figure 2 maps these various inputs – more information about these activities can be found in Annex 1.

Figure 2. SOPHIE Project inputs to the SRA from December 2017 to January 2020

Humans have always interacted with the ocean, using it for food, transportation, recreation and cultural activities, and more recently as a source of energy.

We are now starting to realize that ocean health is also critical for human health and well-being (Depledge et al., 2019; Fleming et al., 2019). While the ocean can benefit humans via resources and services, it can also pose risks such as flooding and pollution. Climate and other environmental change is the most important risk to human health, and although the ocean has so far been instrumental in mitigating this risk, increasing pressure from further global heating will lead to an amplification of risks through increased flooding, storms etc. Some aspects, such as food from the ocean, are both a benefit and a risk.

Europe is intrinsically a maritime continent and European citizens both rely on and are affected by the ocean. We need to better understand and predict this complicated mix of threats, opportunities and their interactions. Exploring these relationships is the basis for an emerging scientific meta-discipline called ‘Oceans and Human Health’ (OHH). This field of research is inherently transdisciplinary, requiring collaboration between medical and public health experts; marine, environmental and social scientists; economists; lawyers; policymakers, citizens and many others.

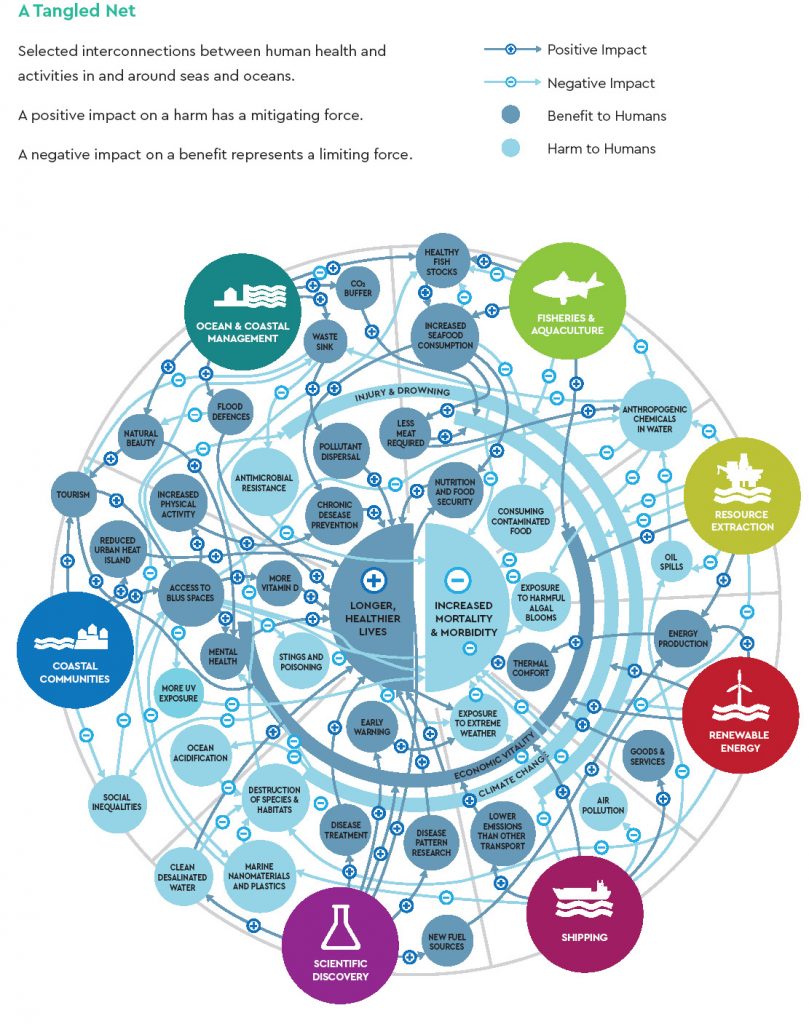

As Figure 3 illustrates, there is not just a one-directional linear relationship between human health and the ocean: instead it is circular, multi-directional and interconnected, with both human health and ocean health being influenced by human behaviour and activity, which is increasingly affecting our oceans.

Figure 3. The circular relationship between human health, human activities and the ocean

Against a background of rising healthcare costs and inequality, and growing populations, it is becoming ever more important to develop a better understanding of the links between oceans and humans, and potential co-benefits.

While an increasing proportion of the healthcare community agree that ‘prevention is better than cure’, only around 7% of healthcare funding in Europe is currently spent on research in prevention and public health (OECD/EU, 2018). Savings could be achieved if the focus was adjusted; and the ocean can support such savings provided these interactions are sustainably managed.

Viewed within the framing of the current political agenda, the inter- and transdisciplinarity of OHH is incredibly important. The Health 2020 European Policy Framework and Strategy for 21st Century (World Health Organization, 2013) identifies “creating resilient communities and supportive environments” as one of four priority areas, and OHH sits comfortably within this remit. In 2015, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development(4) together with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals(5) (SDGs), many of which are directly relevant to OHH including SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 10 (reduced inequality), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), SDG 13 (climate action), SDG 14 (life below water), and SDG 15 (life on land).

It is widely acknowledged that these SDGs cannot be achieved in isolation, and that progress will require true transdisciplinary cooperation: OHH can contribute directly. In the Our Ocean, Our Future: Call to Action arising from the Ocean Conference in 2017(6), the Heads of State and Government expressly recognized that “the well-being of present and future generations is inextricably linked to the health and productivity of our ocean”. The complementary UN Decades for 2021-2030 focusing on Ocean Science for Sustainable Development(7) and on Ecosystem Restoration(8) are a timely opportunity to further increase the attention on and impact of OHH, as the concept of human health are not clearly linked to the health of the ocean in either of the two Decade’s aims.

Recent reports highlight with increasing clarity the links between climate and other environmental changes, the ocean and its ‘health’, and the health of humans (IPCC, 2019). It is clear that the existential threats we face are a product of our own behaviours and choices (e.g. in food consumption, energy use, waste management, and transport). As such we need a far greater understanding of why these behaviours are so resistant to change in the face of overwhelming evidence of their harm both to the natural world and to our own long-term health and well-being – and how they need to be changed as we move towards a low-carbon economy. In this regard, OHH is also highly relevant to the European Green Deal(9) outlined in 2019, which aims to achieve climate neutrality in Europe by 2050. The issues are not merely academic, they are social, political, economic and cultural, and will affect all of humanity. The concept of Planetary Health(10) which frames the health of humans and the planet together, is also growing within the medical and public health communities. OHH is part of this wider environment and health research field, but awareness of this link should be strengthened as it has received relatively little attention to date.

Another issue featuring highly on global agendas is plastics. Growing awareness across the whole of society of plastic pollution has resulted in encouraging measures, including the EU ban on single-use plastics(11). It is noted that empirical links between marine plastic pollution and human health outcomes are still lacking in the literature, and concerns remain risk- rather than evidence-based (Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA), 2019). It is however also crucial to look beyond plastics, to all pollutants (both natural and man-made) in the marine environment, in order to raise awareness and inspire similar decisive political and innovative action.

The interconnections and interrelationships between healthy oceans, human activities and healthy humans, some of which are highlighted in Figure 4, are not well documented or researched. Given the complexity demonstrated in this figure, this is a top research priority. This SRA will delve into these connections in more detail, and highlight some key areas for research.

Figure 4. A tangled net – selected interconnections between human health and activities in and around the seas and oceans (designed by Will Stahl-Timmins, in Fleming et al., (2019))

The Oceans and Human Health landscape

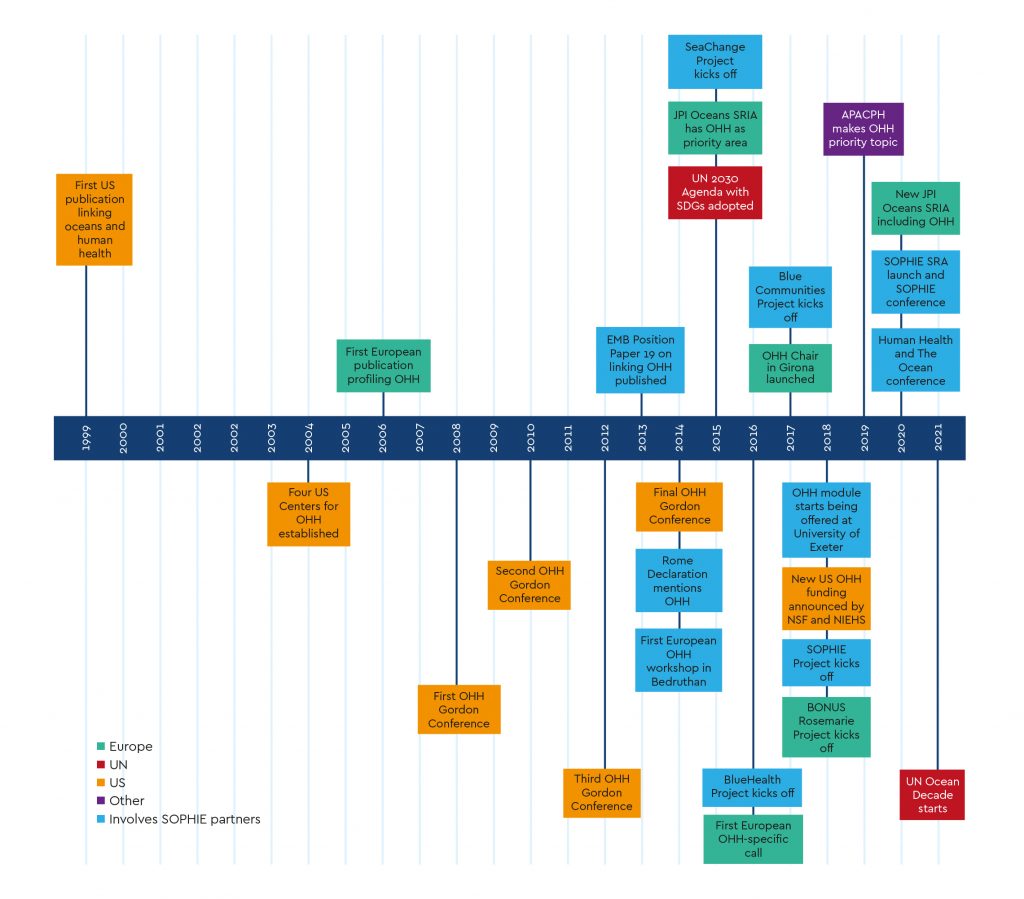

The concept of a meta-discipline known as Oceans and Human Health began to emerge at the turn of the millennium, with publications appearing in the US (Knap et al., 2002; National Research Council, 1999). In the US, where significant funding for OHH research was first awarded, the research has typically focused on addressing key threats to human health from harmful algal blooms (HABs), chemical and microbial pollution, as well as the potential for tackling human health issues through the use of marine natural products (e.g. using marine sponges to develop cancer drugs). In 2018, the USA’s National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) announced a new round of OHH funding with the addition of climate change, demonstrating the continued recognition of the importance of OHH(12).

In Europe, OHH was initially profiled in Marine Pollution Bulletin (Bowen et al., 2006), later by the European Marine Board (Moore et al., 2013); and interest and investment has grown since then, covering a far wider scope of interactions. The research was initially into negative interactions between oceans and humans, but it has more recently expanded to consider positive interactions and the ways in which both could benefit (Depledge et al., 2013). This is evidenced by the recent Horizon 2020 Framework programme funding by the European Commission of projects such as SOPHIE(13), BlueHealth(14), SeaChange(15) and BONUS ROSEMARIE(16), as well as a number of other initiatives, publications and activities. In its Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda for 2015-2020(17), JPI Oceans(18) included “Linking Oceans, Human Health and well-being” as one of 10 strategic areas in which it plans to initiate research funding, and its support for this topic is expected to continue. The BANOS CSA(19) is currently developing its own Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda, of which one of the main pillars is human health, and its key objectives agree with the SOPHIE SRA. The topic of OHH has been fostered through the EurOCEAN conference series(20), with dedicated sessions during the 2014 and 2019 editions as well as an explicit mention in the Rome Declaration (European Marine Board, 2014).

The OHH concept is beginning to gain traction at national level, with projects such as UK Global Challenge Research Fund (GCRF) Blue Communities(21) raising awareness of this topic in East and Southeast Asia. In November 2019, the Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health(22) (APACPH) passed a resolution to make Planetary Health, and in particular OHH, a priority programme. These projects enable OHH professionals across the globe to collaborate, and share ideas and experiences, helping to further develop the field.

The timeline in Figure 5 shows the emergence and development of OHH in Europe and globally.

Figure 5. An OHH timeline showing key milestones in the development of this meta-discipline

What does the literature tell us?

A review of current research provides baseline information that is crucial for underpinning the direction of future research as well as identifying where synthesis of existing evidence is required for policy.

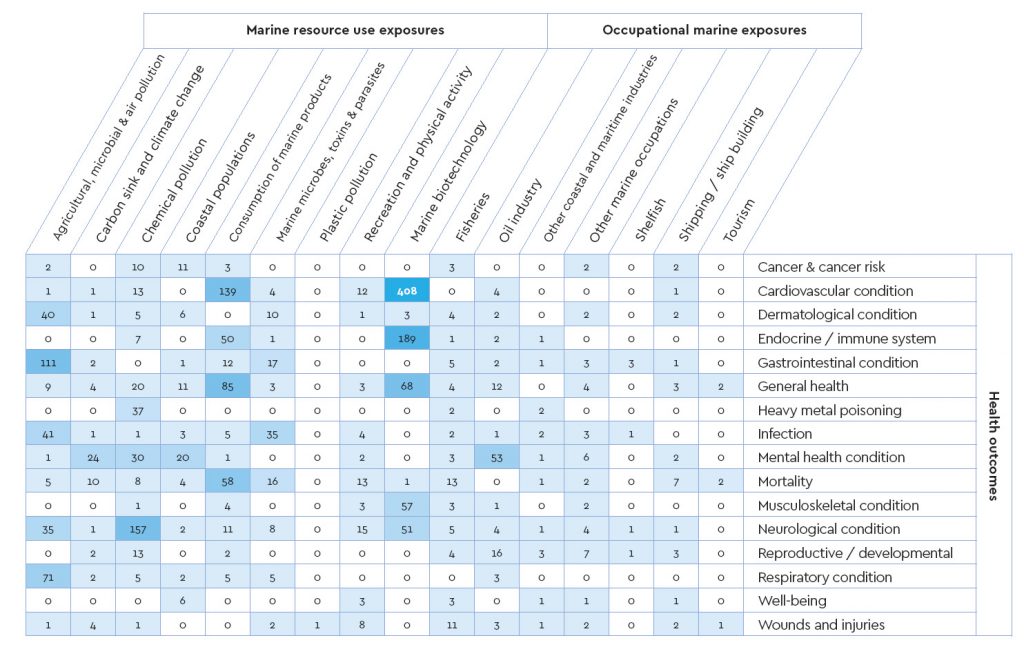

As part of the SOPHIE Project an evidence and literature review(23) was undertaken to understand what links have been researched to date between marine environments and positive and negative impacts on human health and well-being. This review included grey and peer-reviewed literature identified by a systematic search process, and mapped empirical evidence with a defined coastal or marine exposure and a measurable human health outcome. It should be noted that this approach does not give any information about the quality of research or infer any overarching direction of relationships, but presents the research landscape as a whole, helping to identify knowledge gaps and prioritize further syntheses.

Half of the studies examined came from the US. Research was mostly from coastal countries, with particular focus on health impacts linked to activities such as fisheries, oil and gas extraction, shipping, and emergency services. Other notable topics included agricultural and microbial pollution, chemical pollution, coastal habitation, consumption of marine products, coastal recreation, and marine microbes, toxins and parasites. As this review was restricted to measurable health outcomes, it is worth noting that a considerable amount of emerging research was identified where potential risks and opportunities for human health have been identified but where the research has yet to make explicit links, e.g. the impacts of plastic pollution. Figure 6 presents an overview of the numbers of studies for different marine exposure and human health interactions.

Figure 6. Systematic mapping matrix showing the number of articles presenting evidence on each identified interaction between marine exposures and human health outcomes. Papers include synthesized (included in a systematic review) and non-synthesized primary research and grey literature. Dark colours indicate more articles and light colours fewer.

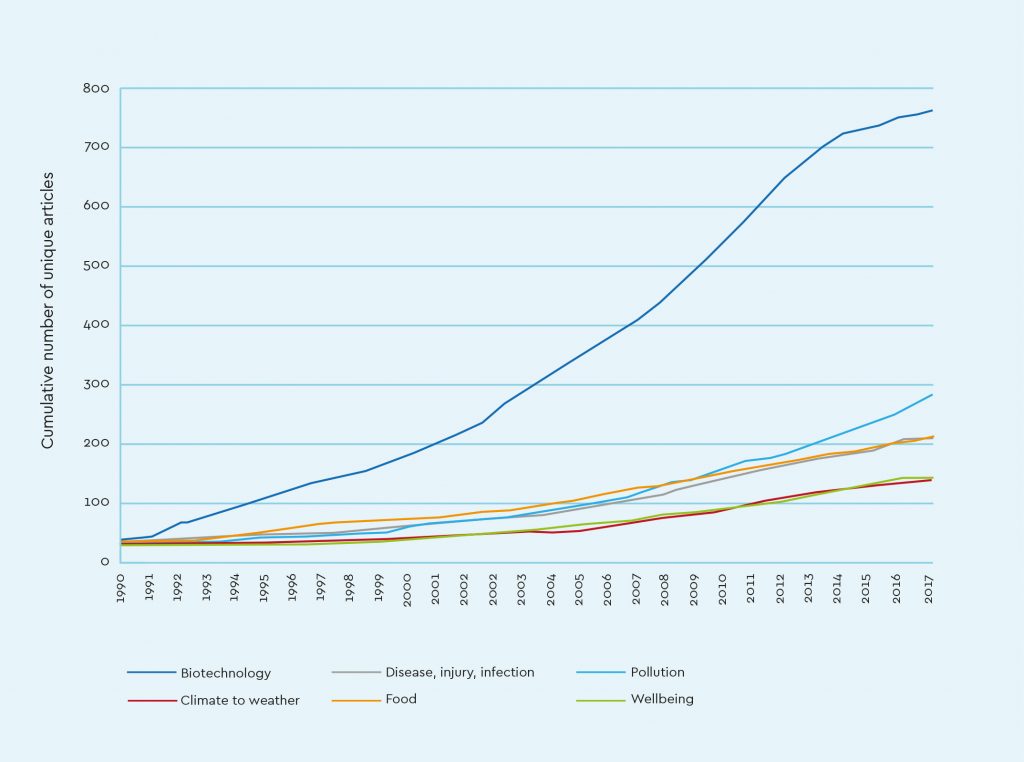

Figure 7 shows the cumulative representation of research over time for six research areas, with Biotechnology identified as the dominant topic. At present, research on positive health outcomes totals roughly half that of negative ones.

Evidence synthesis efforts have been heavily dominated by systematic reviews in marine biotechnology research, particularly related to cardiovascular health. There is some synthesis of evidence on fish-based diets and health, heavy metal pollution and microbial pollution, but many in situ marine health issues are yet to be explored. The mapping exercise has identified a need for formal evidence syntheses in areas such as pollutants and respiratory conditions, mental health outcomes from marine disasters, naturally-occurring marine microbes and changing infection burdens. The exploration of trade-offs is another priority area, e.g. the balance of damaging heavy metal intake vs. the benefits of high-seafood diets.

Figure 7. Timeline of OHH research beginning and growth

Understanding links between research and policy

Current policy approaches can act as barriers to the development of OHH research, therefore we first identify these challenges, and then propose research to address them.

The marine policy landscape works largely at a European level, as it is designed to regulate human activities in and underpin protection of the marine environment, with Directives and other instruments specified for Europe as a whole (Borja et al., 2020; McMeel et al., 2019). Member States implement these nationally and are mandated to report on their approach and progress.

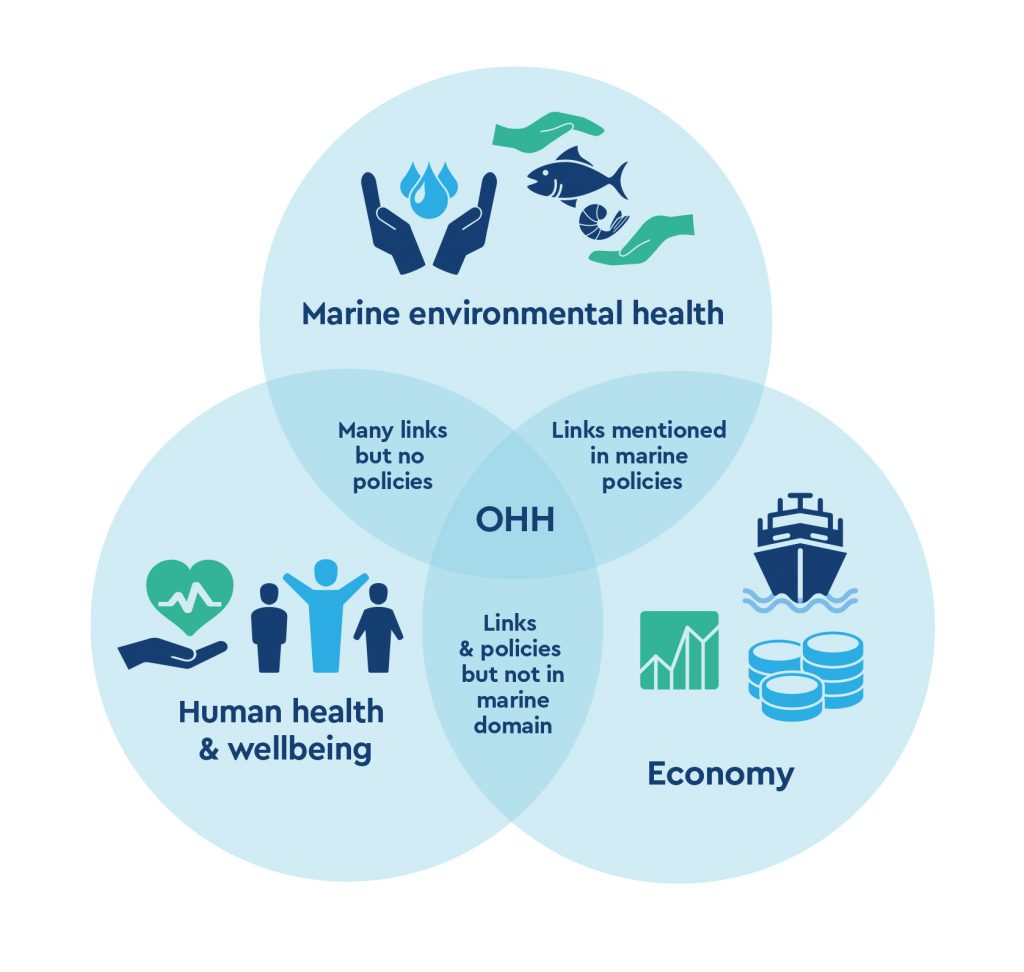

Clearly, marine issues themselves (e.g. pollution and marine life) are not constrained by national boundaries but instead travel freely through Europe and beyond. In contrast, Member States are primarily responsible for health services and medical care, therefore at European level health policy aims to protect and improve the health of EU citizens and complements national policies. The Europe-wide health policies that do exist do not generally have the same regulatory weight as those of marine policies. Coupled with the relatively recent increase in awareness around OHH, this means that at present there are no policies in Europe that explicitly cover both oceans and human health. Examples that do overlap, such as the Bathing Water Directive(24), are limited in scope and in the risks addressed. This poses challenges to both the research and policy communities. Figure 8 presents an overview of the status of policies relating to OHH.

Figure 8. Overview of current policies relating to OHH, and their interaction

The first challenge for the research community is that OHH does not clearly sit within a single policy remit, at either European or national level. This can make the funding of research more difficult, and communication pathways for needs and results unclear. The OHH research community could help to address this challenge by further raising awareness of OHH and research policy gaps at all relevant policy levels.

The second challenge is a resulting lack of data (and a lack of availability of existing data) linking both oceans and human health, especially in emerging areas such as new pollutants. This is a challenge for policymakers attempting to devise integrated policies because the evidence of cause and effect relationships is lacking. In the near future, the OHH research community should further explore what relevant data are already available and being collected under which frameworks, identify data which could easily be collected under existing monitoring and observation programmes, propose new indicators of both human and ocean health, and create a body of evidence to better link cause and effect in support of policymaking.

A third challenge lies in what different stakeholders expect from these policies and other governance approaches. In the various stakeholder interactions that took place within the SOPHIE Project (see Annex 1), citizens tended to prioritize measures based on accountability within industry, whereas other stakeholders tended more towards regulatory and governance systems. Traditional top-down policy measures play an important role and will always be required, but they are not the only solution. Increasingly, science, policymakers and citizens themselves are also recognizing the importance of bottom-up and local initiatives. This is especially relevant given the diversity of people and marine environments in Europe. Some issues will have greater importance in some sea-basins and/or countries than others; and the appropriate solutions will vary depending on where, at what scale, and by whom they are being implemented. In this regard, the OHH research community can support policy by further exploring ways in which this dual approach of top-down and bottom-up measures could be achieved, identifying key stakeholder groups for different areas of interest and developing specific best practice approaches for ensuring stakeholder and citizen input for informing policy.

Citizen and stakeholder priorities

During the course of the SOPHIE project, stakeholders and citizens acknowledged and appreciated the links between the ocean and human health, but indicated that they need to know more about these links to provide meaningful input to policy and decision-making.

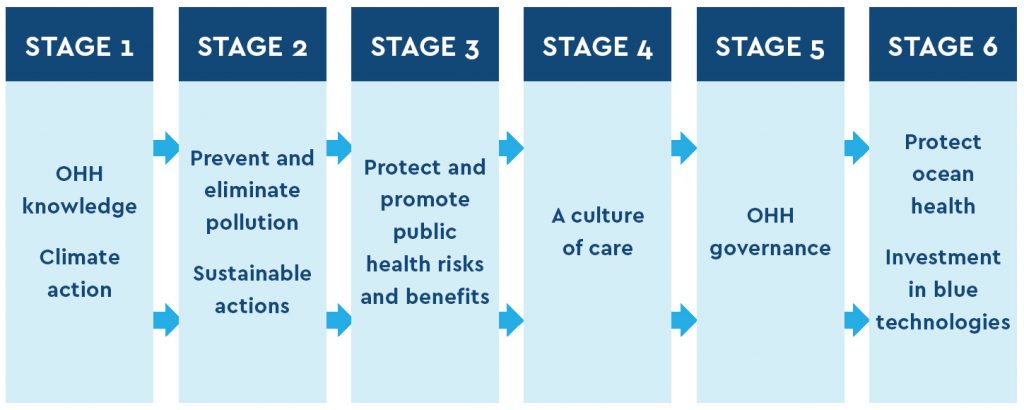

In the societal stakeholder and citizen workshops to build consensus around priorities and solutions for OHH , they recognize the gaps between the descriptions of OHH(25) and understanding the causal processes that drive OHH dynamics (McHugh et al., 2020). In the priorities that stakeholders and citizens identified for OHH, the nine themes presented in Figure 9 were perceived to be the most influential for Europe.

In this map, the Stage 1 themes are perceived to have the greatest influence on the subsequent themes and on OHH generally, while the Stage 6 themes are perceived to be the most impacted by processes and outcomes of the preceding themes and to have a lower level of influence on OHH.

In terms of research and successful mobilisation action, the themes to the left of the map are more likely to have a stronger impact on “the overall system of priorities” (Domegan et al., 2014) while at the same time relieving pressure on the priorities belonging to the themes on the right. It is important to be aware that this influence map is not to be considered an action plan, since other factors may also come into play when deciding on actions to be taken. It is not necessary to address OHH knowledge first if there is an immediate opportunity e.g. to address pollution (Stage 2) or protect the public from health risks (Stage 3).

Figure 9. Meta-analysis map showing responses to the question, “What, in your opinion, are the top priorities for protecting public health and the health of the marine environment for a sustainable future?”

The map suggests, however, that the chance of a successful outcome might be greater if the priorities for OHH knowledge were implemented at the same time. No matter where research is conducted and/or the initial action is taken, the map can advise us on the possible impact of research and mobilisation actions, as well as priorities that will have an effect on their success, and hence can serve as an invaluable planning tool. This map highlights a need to link knowledge with practice in a way that can support and promote sustainable actions and greater citizen engagement. This presents opportunities for transdisciplinary research and partnership building between research scientists in OHH and marine science, social sciences and public health.

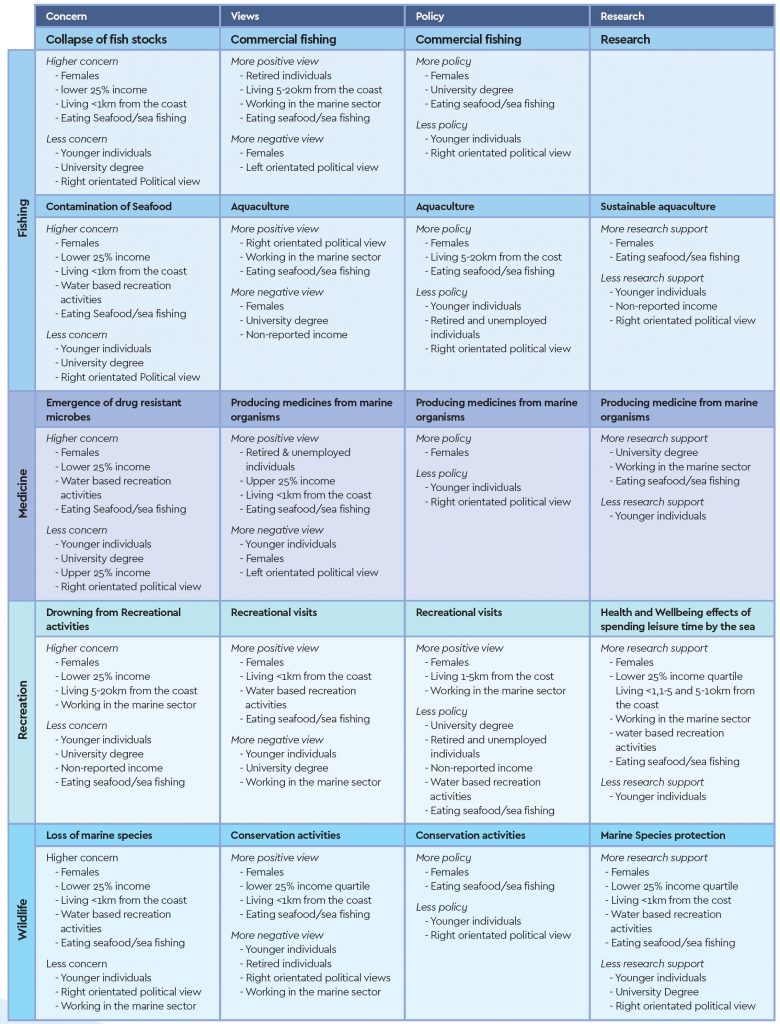

The SOPHIE Survey(26) delved into the opinions of over 14,000 European citizens, to find out more about their feelings regarding marine activities relating to topics including those linked to the three target action areas of this SRA. Figure 10 below outlines the main results. It was found that citizens believe that they place more importance on the environment and on health than policymakers do, while policymakers place more importance on the economy.

Figure 10. Summary of the main results of the SOPHIE Survey

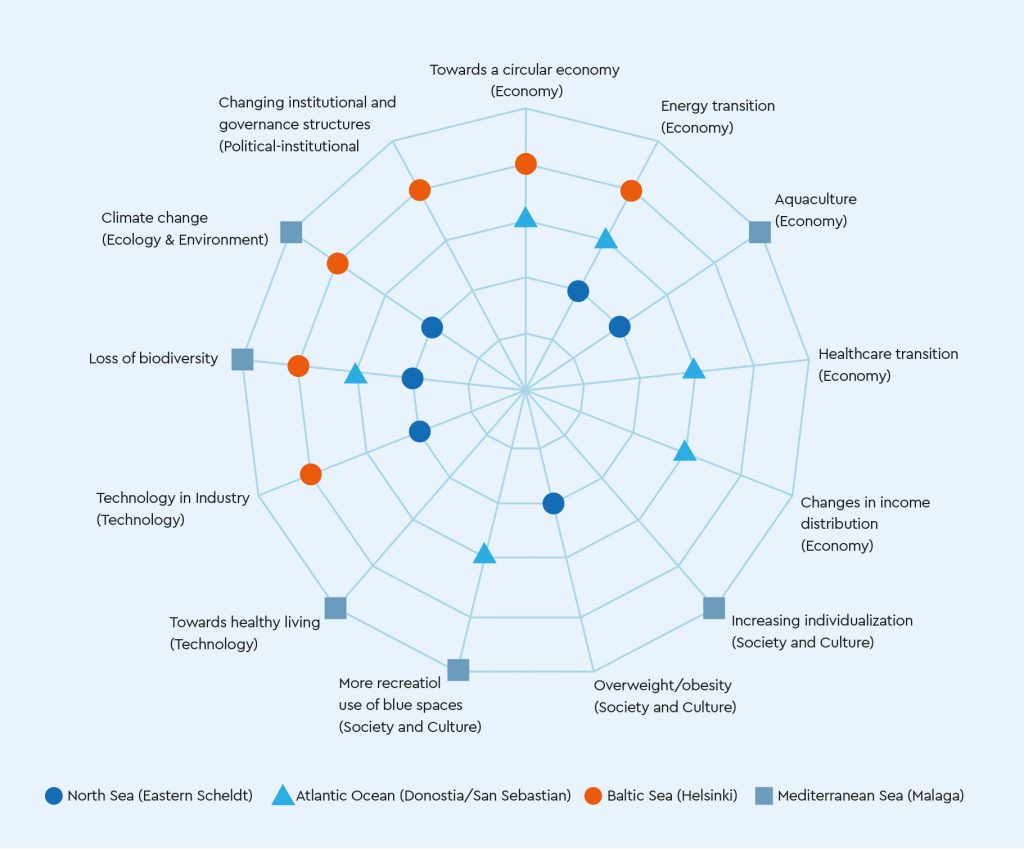

The importance placed by citizens on given activities was explored in European regional workshops(27) that focused on identifying trends and priorities that could be important for OHH into the future. In each of the four sea basin workshops, the attendees were asked to agree on their top six trends for their sea basin, and the results can be seen in Figure 11 below.

Figure 11. Trends identified as most relevant by the participants for the sea basin being discussed

During a case study in the Eastern Scheldt (Netherlands) the current practices of, and future challenges for, local stakeholders were investigated. Here, the level of collaboration between different stakeholders varied depending on the issue in question, but having a broad range of policies covering a particular issue was not seen as a barrier. The participants noted that they are concerned about emerging contaminants, and felt that at present, the human health implications of these contaminants were not being taken explicitly into account as existing policies do not yet address these substances. A better understanding of interactions is needed: however, gathering these data through monitoring alone could be too costly and time-consuming. Modelling as a means to develop understanding of OHH interactions was proposed.

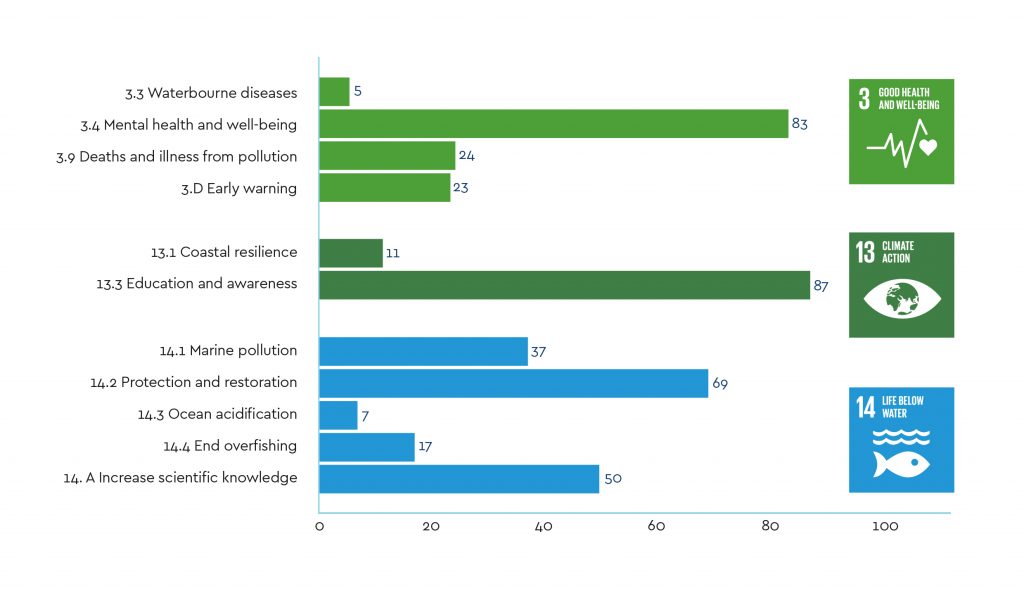

Clear priorities emerged from the SOPHIE inventory of innovative initiatives(28) that have been developed and which link to OHH. The environmental issues that were most commonly addressed by local bottom-up initiatives were marine litter and loss of biodiversity. There were also many citizen science projects, and other initiatives to enhance human health through marine ecotourism and therapies involving exercise at sea. Figure 12 highlights the numbers of initiatives that are in line with relevant SDGs. The impact of such innovative initiatives could further increase if local initiatives collaborated in larger networks to share experiences, and collect data and resources.

Figure 12. Number of innovative initiatives in the SOPHIE inventory contributing to relevant sustainable development goals